Three Stages of Existentialism

Humans in Anguish: "The man who involves himself and who realizes that he is not only the person he chooses to be, but also a law-maker who is, at the same time, choosing all mankind as well as himself, cannot help escape the feeling of his total and deep responsibility. Of course there are many people who are not anxious; but we claim they are hiding their anxiety, that they are fleeing from it....Anguish is evident, even when it conceals itself."

Humans in

Forlornness: "When we speak

of forlornness, we mean only that God does not exist and that we have to face

all the consequences of this....The existentialist thinks it very distressing

that God does not exist, because all possibility of finding values in a heaven

of ideas disappears along with Him; there can no longer an a priori Good, since

there is no infinite and perfect consciousness to think it. Nowhere is it written that the Good exists,

that we must be honest, that we must not lie; because the fact is we are on a

plane where there are only men....Neither within him or without does man find

anything to cling to. He can't start

making excuses for himself.

We are called upon to live without appeal, as appeals are intellectually dishonest. But perhaps there are other alternatives than: 1) accepting absurdity; 2) embracing hopeful metaphysics; or 3) Camus’ defiance. Perhaps we can just say we don’t understand life at all, but we affirm it anyway. We just try to live without being sure of anything. Be open to possibilities. Then we might ground the meaning of our lives in the small part we can play in bringing about a more meaningful reality, by working to transform reality. This is no answer, but a way to live

Humans in Despair: "As for despair, the term has a very

simple meaning. It means that we shall

confine ourselves to reckoning only with what depends upon our will, or on the

ensemble of probabilities which make our action possible....No God, no scheme,

can adapt the world and its possibilities to my will."

Summary of The Myth of Sisyphus

Summary: In The Myth of Sisyphus (1955) Camus claims that the only important philosophical question is suicide—should we continue to live or not? The rest is secondary, says Camus, because no one dies for scientific or philosophical arguments, usually abandoning them when their life is at risk. Yet people do take their own lives because they judge them meaningless, or sacrifice them for meaningful causes. This suggests that questions of meaning supersede all other scientific or philosophical questions. As Camus puts it: “I therefore conclude that the meaning of life is the most urgent of questions.”

What interests Camus is what leads to suicide. He argues that “beginning to think is beginning to be undermined … the worm is in man’s heart.”When we start to think we open up the possibility that all we valued previously, including our belief in life’s goodness, may be subverted. This rejection of life emanates from deep within, and this is where its source must be sought. For Camus killing yourself is admitting that all of the habits and effort needed for living are not worth the trouble. As long as we accept reasons for life’s meaning we continue, but as soon as we reject these reasons we become alienated—we become strangers from the world. This feeling of separation from the world Camus terms absurdity, a sensation that may lead to suicide. Still most of us go on because we are attached to the world; we continue to live out of habit.

But is suicide a solution to the absurdity of life? For those who believe in life’s absurdity it is a reasonable response—one’s conduct should follow from one’s beliefs. Of course conduct does not always follow from belief. Individuals argue for suicide but continue to live; others profess that there is a meaning to life and choose suicide. Yet most persons are attached to this world by instinct, by a will to live that precedes philosophical reflection. Thus, they evade questions of suicide and meaning by combining instinct with the hope that something gives life meaning. Yet the repetitiveness of life brings absurdity back to consciousness. In Camus’ words: “Rising, streetcar, four hours in the office or factory, meal, four hours of work, meal, sleep, and Monday, Tuesday, Wednesday, Thursday, Friday, and Saturday…”Living brings the question of suicide back, forcing a person to confront and answer this essential question—should I go on?

Yet of death we know nothing. “This heart within me I can feel, and I judge that it exists. This world I can touch, and I likewise judge that it exists. There ends all my knowledge, and the rest is construction.”Furthermore I can’t know myself intimately anymore than I can know death. “This very heart which is mine will forever remain indefinable to me. Between the certainty I have of my existence and the content I try to give to that assurance, the gap will never be filled. Forever I shall be a stranger to myself …” We know that we feel, but our knowledge of ourselves ends there.

What makes life absurd is our inability to know ourselves and the world’s meaning even though we desire such knowledge. “…what is absurd is the confrontation of this irrational and the wild longing for clarity whose call echoes in the human heart.” The world could have meaning: “But I know that I do not know that meaning and that it is impossible for me just now to know it.” This tension between our desire to know meaning and the impossibility of knowing it is a most important discovery. In response, we are tempted to leap into faith, but the honest know that they do not understand, and they must learn “to live without appeal…” In this sense we are free—living without higher purposes, living without appeal. Aware of our condition we exercise our freedom and revolt against the absurd—this is the best we can do.

Nowhere is the essence of the human condition made clearer than in the The Myth of Sisyphus. Condemned by the gods to roll a rock to the top of a mountain, whereupon its own weight makes it fall back down again, Sisyphus was condemned to this perpetually futile labor. His crimes seem slight, yet his preference for the natural world instead of the underworld incurred the wrath of the gods: “His scorn of the gods, his hatred of death, and his passion for life won him that unspeakable penalty in which the whole being is exerted toward accomplishing nothing.” He was condemned to everlasting torment, and the accompanying despair of knowing that his labor was futile.

Yet Camus sees something else in Sisyphus at that moment when he goes back down the mountain. Consciousness of his fate is the tragedy; yet consciousness also allows Sisyphus to scorn the gods which provides a small measure of satisfaction. Tragedy and happiness go together; this is the state of the world that we must accept. Fate decries that there is no purpose for our lives, but one can respond bravely to their situation: “This universe henceforth without a master seems to him neither sterile nor futile. Each atom of that stone, each mineral of that night-filled mountain, in itself forms a world. The struggle itself toward the heights is enough to fill a man’s heart. One must imagine Sisyphus happy.

Reflections – Camus argues that life is meaningless and absurd. Still we can revolt against the absurdity, and find some small modicum of happiness. Essentially Camus asks if there is a third alternative between acceptance of life’s absurdity or its denial by embracing dubious metaphysical propositions. Can we live without the hope that life is meaningful, but without the despair that leads to suicide? If the contrast is posed this starkly it seems an alternative appears—we can proceed defiantly forward. We can live without faith, without hope, and without appeal.

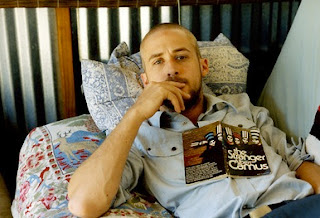

Ryan Gosling reading Camus!

Ryan Gosling in La La Land!

Camus says, "What does it all mean, Ryan Gosling?"

Now that I have read the summary of “The Myth of Sisyphus,” I understand what Camus is trying to explain through the character Meursault. Camus’ main question is, “Can we live without the hope that life is meaningful, but without the despair that leads to suicide?” He uses Meursault to explain his theory of absurdism that “We can live without faith, without hope, and without appeal.” Meursault does not really have any reason to live, nor does he have any reason to die. His entire life as told by himself shows that he continues “to live out of habit.” He wakes up, goes to lunch at Celeste’s, meets up with Marie, cooks dinner, and spends the night with Marie. Every day is mundane, and everything is the same as everything else. When Marie asks him if he loves her, he says, “it didn't mean anything but that I didn't think so.” Marie in this situation represents the readers, who feel confused and sad at his response, but for Meursault, life is meaningless and so he is separated from the world, unable to be understood by others.

ReplyDelete“The Myth of Sisyphus,” which is about a man named Sisyphus who perpetually rolls a rock to the top of a mountain just for it to roll back down, is very similar to the life of Meursault. He has a daily routine that he follows out of habit, and although he already knows that he will never be successful nor satisfied, he still “rolls the rock back up.” When he is on the beach looking at the Arab, he thinks, “It was this burning, which I couldn't stand anymore, that made me move forward. I knew that it was stupid, that I wouldn't get the sun off me by stepping forward.” Many times in the novel he complains about how the sun is too hot, but that he cannot escape it. Despite knowing that the scorching sun will not go away, he still takes walks on the beach.

This idea of absurdism is similar to existentialism in that they both describe humans as being lonely. Existentialism states that humans must make decisions for themselves, without the help of God or the help of others. Their life is the outcome of the decisions they make for themselves. In some ways, being fully responsible for one’s own life gives freedom to the individual, but it also brings much despair. According to absurdism, life is meaningless because of “our inability to know ourselves,” and once we realize this, we become a stranger to the world. However, Camus says that even when life seems meaningless, we can still live enjoying the little things that bring happiness.

Based on this portion of the book I’ve come to understand that Meursault is probably a bit of a sociopath. It wasn’t all that clear before, considering he has platonic relationships and feels morally obligated to attend his mother’s funeral, but Meursault is very despondent from the world. He observes things rather than participating in them. I think Meursault recognizes this about himself, which is why when he finally begins to feel happy around Marie it is so meaningful to him. It was perhaps the first time he actually felt something positive and passionate for another person. Despite his short-lived happiness around Marie, Meursault becomes a killer at the end of Chapter 6 when he kills a man using Raymond’s revolver. The scene, which might I mention is narrated by Meursault himself, brushes over the death rather quickly and mostly focuses on Meursault’s discomfort in the extreme heat of the beach. He makes it seem like the incident was out of self defense, however, after recognizing that by killing a man he has ruined his chances for happiness, Meursault brutally shoots him four more times as a big “screw you!” to the dead man’s corpse. Whatever character development he might have experienced by being with Marie and strengthening his relationships with other people went straight down the drain after this moment. “The trigger gave; I felt the smooth underside of the butt; and there, in that noise, sharp and deafening at the same time, is where it all started. I shook off the sweat and sun. I knew that I had shattered the harmony of the day, the exceptional silence of a beach where I'd been happy. Then I fired four more times at the motionless body where the bullets lodged without leaving a trace. And it was like knocking four quick times on the door of unhappiness.” (59) Camus, in his Myth of Sisyphus, emphasizes the importance of individuals being able to embrace the absurd conditions of human existence. This will in turn promote a life filled with willful and exciting experiences. I believe Meursault follows this way of thinking, but to an extreme. He thinks that the human condition is absurd, but instead of accepting life as it is and embracing this absurdity he ends of just wanting to observe the craziness of other people’s lives instead of focusing on his own. This in turn makes it hard for him to experience very many willful things.

ReplyDeleteThe Stranger is an example of how Camus’s theory of the absurd can manifest in a person. Meursault is the medium that Camus uses to convey his theory. Meursault does not seem to care about anyone or anything. He is the epitome of someone who “goes with the flow”. He seems to be constantly trying to find a meaning in his life, but he can never muster the will to care about anything. He has no passion, no interests. He simply goes through his daily routine over and over again. Ironically enough, this disinterest does not really affect any of the characters. Marie is not particularly destroyed when Meursault says he does not love her, but rather seems to accept that that is just the way Meursault is. It is almost as if Meursault’s absurdism has rubbed off on the people around him. He does not really care about anything, so the people around him cannot form strong bonds with him, which means they cannot empathize with him. Meursault is, essentially, going through a life long existential crisis. He has no purpose and is searching for life’s meaning. This is how the theory of the absurd and existentialism connect. An existentialist is someone who accepts the theory of the absurd. The existentialist accepts the world as it is, and values only what they themselves have given value. By accepting the theory of the absurd, one accepts that nothing has intrinsic value or meaning, and therefore we ourselves give things value and meaning. This is why someone who does not accept the theory has an “existential crisis”. They are searching for someone to give them meaning, while only they can give things value. Knowing this can show someone how to live the life they want to. Essentially, the message of Camus’s theory and existentialism is that no one will do anything for you. You make life what it is. This is also why people often come out of an existential crisis with different values. The crisis might be triggered by a sudden questioning and rejection of many of the values that one may have been taught. A person comes out of the crisis with values that they have made for themselves, resolved to the knowledge that only they can give their own live value. This lesson is very important in the real world because it can be applied to almost anyone. The factory worker must put value in something in their life, otherwise they will have no reason to live. This also applies to people who will never have to work a day in their lives. This lack of responsibility can cause one to lose value in things because they have no needs. By putting value in something such as a sport they have gained a reason to live. Often enough, we only live because we are seeking something which we value, which is how the theory of the absurd, existentialism, and conflicts surrounding suicide in The Myth Of Sysiphus all tie together.

ReplyDeleteA passage that stuck out the most to me in this book so far is the conclusion of chapter 6:

ReplyDelete“The trigger gave; I felt the smooth underside of the butt; and there, in that noise,

sharp and deafening at the same time, is where it all started. I shook off the sweat and sun. I knew that I had shattered the harmony of the day, the exceptional silence of a beach where I’d been happy. Then I fired four more times at the motionless body where the bullets lodged without leaving a trace. And it was like knocking four quick times on the door of unhappiness” (59).

This passage really resonated with me because it demonstrated such a stark contrast in Meursault’s actions. Up until this point, Meursault has appeared as a rather bland character in which he expresses little to no emotion at all ever. Even when he is with Marie, someone who it appears that he cares for, a woman he may potentially marry, he still does not show anything different than his monotone personality. Whether or not he marries Marie doesn’t make “any difference” to him. Meursault even goes as far as to admit to Marie that he “probably didn’t love her” but would marry her so long as it made her happy. This is extremely alarming to most people because even though he is surrounded by someone who loves him so dearly, he is still incapable of having a change in any of his thoughts or emotions. None of it appears to matter to him, none of it is special to him, it is rather simply just there. At the end of chapter 6 however, there is a drastic shift in Meursault’s personality. No longer is everything bland, and monochromatic, but rather a burst of color and emotions enter his world. He begins to feel things in the sense that he is able to understand and view the results of his actions as something that is bad. Previously, Meursault was incapable of doing so, having little to no desire to help the people he was hurting, such as Raymond’s girlfriend when she was getting beaten or Salamone’s dog that was getting scolded and thrown around. The line from this passage in which Meursault acknowledges the “harmony of the day” has been shattered demonstrates growth in Meursault’s life and at the same time displays a glimpse of hope. This hope however does not last long for in the next line Meursault continues on with the bad behavior and shoots the man four more times. This is crucial because Camus demonstrates how people who are lonely and suffering while living through the motions of life as if they are robots, can indeed have moments of humanity, these moments however are short lived and do not last long.

Camus argues that “life is meaningless and absurd.” and that we can somehow “live without the hope that life is meaningful, but without the despair that leads to suicide.” He proves his theory through Meursault. He lives the meaningless and absurd life that Camus describes, and he does not seem hopeful or content with his life, but at the same time, he does not seem to be in complete despair that his life has no purpose. The sense of hopelessness comes from his actions or lack thereof. Some can argue that Meursault’s lack of interaction with his environment makes his life seem meaningless or that because his life is pointless, he chooses not to involve himself in anything. The argument can go both ways and they both kind of make sense. But I think in a world where many people are hopeful and believe that their life has meaning, Meursault is one of the few that goes against the social norm of living to be happy and content, which makes him fit Satre’s description of humans in despair. “No God, no scheme, can adapt the world and its possibilities to my will.” Nothing Meursault does going to make a significant effect on the world around him, and whatever the world is doing is not going to affect him.

ReplyDeleteI feel in some ways; The Stranger describes the lives of the majority of the population. Many people have a monotonous daily routine that they do until they die, and they have boring desk jobs, and its only purpose is to put food on their tables. Many of us go to school and then get a job to survive until we ultimately die. There is no real meaning to what we do every day. Though there are the few that are doing big things and are living their best lives and their lives are not based on a daily routine. But that only the one percent gets that luxury and in the end they still die, and we do not know what happens after that. So is it worth it to try and be apart of the one percent knowing we all end in the same place? I think yes. I would rather have a meaningful life, filled with great adventures and memories, mainly because I do not know what happens after I die. I might not get a second chance at a new life, or I might, who knows. But I would rather die feeling happy and content with what I have achieved in life than feeling absolutely nothing.

While Chapters 1-3 of The Stranger are quite depressing, chapters 3-6 bring the piece to a whole new level. In contrast to the first section, this part seems to be focused on the changes going on in Meurault’s life. His neighbor’s dog goes missing. His boss offers him a new job in Paris, to which he replies saying “that people never change their lives, that in any case one life was as good as another and that I wasn't dissatisfied with mine here at all.” He still remains quite emotionless, yet on the beach at Masson’s house, the burning heat seems to awaken a certain animalistic anger within him. With a glint of silver, this anger erupts, with truly horrific consequences.

ReplyDeleteIn the summary of The Myth of Sisyphus, Camus claims that the “only important philosophical question is suicide—should we continue to live or not?” This mentality, while incredibly pessimistic, (depending on the lens from which it is viewed) has an odd sense of truth within it. "“He argues that “beginning to think is beginning to be undermined … the worm is in man’s heart."When we start to think we open up the possibility that all we valued previously, including our belief in life’s goodness, may be subverted. This rejection of life emanates from deep within, and this is where its source must be sought. For Camus killing yourself is admitting that all of the habits and effort needed for living are not worth the trouble."" In The Stranger, Meursault seems to be battling with this question throughout the story. While he appears to be emotionless, I believe that it is because he represents Camus’ idea of pure philosophy: the only thing he really concerns himself with is the value of life, for he doesn’t care for love, mourning, or empathy. When he shoots the man on the beach, he gives in to this philosophical argument, and in a way, “kills himself”, or at least kills the person he used to be by killing another. As Meursault himself puts it, the four bullets he fired at a lifeless body were “ like knocking four quick times on the door of unhappiness. “

According to the summary, “Camus argues that life is meaningless and absurd. Still we can revolt against the absurdity, and find some small modicum of happiness.” This theory of the absurd was evident throughout The Stranger. No character better demonstrates this theory than Meursault. He shows so little interest in so many different aspects of his life that it is concerning. At the beginning of the book, he reveals his mother is dead, yet he doesn’t even know the date which she died; he says “Maman died today. Or yesterday maybe, I don't know...That doesn’t mean anything.” Raymond explains to him a sickening scheme designed to get revenge on an ex-girlfriend of his, and he doesn’t react to it. This actually leads to Raymond asking for his help, whoch he agrees to give: “Since I didn't say anything, he asked if I'd mind doing it right then and I said no.” Later on, Marie asks if he loves her, and he said “it didn’t mean anything”. Marie even goes on to propose, and he shows no emotions at all, saying it didn’t make any difference to him; he would if she wanted to. Lastly, he ends up shooting an Arab man multiple times; taking his life without the slightest pity, saying “I fired four more times at the motionless body where the bullets lodged without leaving a trace. And it was like knocking four quick times on the door of unhappiness.” He even seemingly made it seem to be some kind of accident with the gun, claiming “The trigger gave”. In short, in situations where normal people would typically show sadness, excitement, discomfort, regret, etc, all Meursault shows is indifference.

ReplyDeleteCamus’ theory also stated that “Still we can revolt against the absurdity, and find some small modicum of happiness.” Even this seemed to be demonstrated by Mersault; the only time where Meursault seems to be deviate from his normal, emotionless self is when he spends time with Marie.

To me, the expression of absurdity in the Stranger has to do mainly with Meursault’s indifference. He is sort of the end of line for the thought process that Camus talks. He knows nothing of anything, feels nothing for anyone, and feels futility in his every action. He lives a life with no agency whatsoever. Not only is he the ultimate yes man, he is cognizant and indifferent to the fact of who he is. I think the implication is that on the inside, we are all like Meursault and we have just yet to realize it. The choices we make never really matter, we were doomed to make them from the start. We attach false meaning to what happens to us and what we happen to do to convince us away from the hopelessness of Meursault. While Meursault's lack of emotion differentiates him from us tragically, it clears up his point of view. With his lack of tinted glasses, he sees the world for what it is, behind the layers of society, religion, relationships and such that keep us going. His shooting of the Arab, is, I suppose, his act of rebellion. He revolts by tearing himself off the tracks of his life, by creating an absurdity. Camus and Satre have strongly conflicting schools of thought. The personal responsibility that Satre claims is the source of our despair is completely at odds with Camus's claim that life is absurd and pointless. Despite the fact that Camus revolts by taking life into one’s own hand, it has nothing to do with taking responsibility for the future and betterment of humanity. Furthermore, I find Camus comparatively inapplicable to our lives. While Satre’s self agency puts weight into our thought in a way that should improve humanity, Camus’s rebellion is of self satisfaction, and requires rejecting conventional happiness for woke contentment.

ReplyDeleteIn the summary, “Camus argues that life is meaningless and absurd. Still we can revolt against the absurdity, and find some small modicum of happiness.” This theory of the absurd was shown throughout The Stranger. No one better demonstrates this theory than Meursault. He shows so little interest in so many different aspects of his life that it is concerning. At the beginning of the book, he reveals his mother is dead, yet he doesn’t even know the date which she died; he says “Maman died today. Or yesterday maybe, I don't know...That doesn’t mean anything.” Raymond explains to him a sickening scheme designed to get revenge on an ex-girlfriend of his, and he doesn’t react to it. This actually leads to Raymond asking for his help, whoch he agrees to give: “Since I didn't say anything, he asked if I'd mind doing it right then and I said no.” Later on, Marie asks if he loves her, and he said “it didn’t mean anything”. Marie even goes on to propose, and he shows no emotions at all, saying it didn’t make any difference to him; he would if she wanted to. Lastly, he ends up shooting an Arab man multiple times; taking his life without the slightest pity, saying “I fired four more times at the motionless body where the bullets lodged without leaving a trace. And it was like knocking four quick times on the door of unhappiness.” He even seemingly made it seem to be some kind of accident with the gun, claiming “The trigger gave”. In short, in situations where normal people would typically show sadness, excitement, discomfort, regret, etc, all Meursault shows is indifference. Camus’ theory also stated that “Still we can revolt against the absurdity, and find some small modicum of happiness.” Even this seemed to be demonstrated by Mersault; the only time where Meursault seems to be deviate from his normal, emotionless self is when he spends time with Marie.

ReplyDeleteAfter the first 3 chapters, these chapters were much less depressing. He says,“beginning to think is beginning to be undermined … the worm is in man’s heart"(Camus). When we start to contemplate further into life, we can start to second guess our previous beliefs, which opens up te door to indecisciveness. People can began to reject their own opinions on life, and began to search for real meaning, Camus thinks that people shouln’t be doing this, and that they should just accept life as it is, and live without wonder. Some may argue that Mersault struggles with this throughout the story, however I think that Mersault is perfectly content. He is emotionless throughout the story and seems to accept everything, this is the picture perfect way that a mentally stable, happy person would look at the world. When Mersault shoots the man on the beach, he seems to be unphased by it. While most people would have a reaction to this, and begin to rethink their choices, Mersault seems to just continue on like it was normal. After this incident, Mersault says that shooting at that lifeless body was,“Like knocking four quick times on the door of unhappiness”(Camus). Camus’s theory is that individuals should embrace the absurd condition of human existence, Mersault is the embodiment of this theory. Mersault accepts everything that comes his way, both good and bad.This part is more about what is actually going on with Mersault rather than his emotions. He is offered a new job, however he still does not express much emotion about it. His pessimistic attitude seems to express Camus’s theory that humans should embrace the absurd condition of human existance. Mersault treats life with a certain disconnect, which seeps though him making it plainly clear that he is a sociopath.

ReplyDeleteCamus draws two parallels of living: we are either connected to life and live it fully, or we are in the “absurd”. Life is not a matter of whether or not we enjoy life, or whether or not we want to die; it’s how we define our lives in the way we live them. Meursault lives absurdly. The only emotions he feels are discomfort, like with the sun or with things people do that annoy him, or the driving force of the fact that another day comes. He just lives. Even while still supposed to be in mourning, he only considers how he “had to get up early the next morning” (p39). Even in his job, his boss tells him that he, “had no ambition, and that that was disastrous in business” (p41). Although he’s a complex character, he views the world without any complexity. Everything is the same to him because he has nothing to live for. He is for the sake of other people. He protects Raymond repeatedly, not considering the terrible moral implications of his actions. He even kills a man for Raymond! The man is a sociopath, like a blank slate that other people can write on. With the woman he’s supposed to love, he “said it didn't make any difference to me and that we could [marry] if she wanted to. Then she wanted to know if I loved her. I answered the same way I had the last time, that it didn't mean anything but that I probably didn't love her” (p41). Meursault has no emotion for anyone in his life. He’s like an emotional tumbleweed, drifting through the wind that is created by others in his social circle. Camus says that “We know that we feel, but our knowledge of ourselves ends there”, yet Meursault feels nothing. He doesn’t know himself. He’s a personification of the absurd.

ReplyDeleteThe ending of Part 1 wasn't entirely surprising. I thought there would be one point where Meursault finally broke down - a lot has been going on. His mother died, he entered a new relationship, now these Arab men are following him around. Despite all of this, he failed to show any reaction or emotion in response to these events and developments. I think that all of this built up and finally caused him to break - however, he doesn’t exactly seem that emotionally stressed after he murders the Arab man. He doesn’t act like a killer, he doesn’t feel guilty.

ReplyDelete“Camus claims that the only important philosophical question is suicide—should we continue to live or not? The rest is secondary, says Camus, because no one dies for scientific or philosophical arguments, usually abandoning them when their life is at risk. Yet people do take their own lives because they judge them meaningless, or sacrifice them for meaningful causes. This suggests that questions of meaning supersede all other scientific or philosophical questions. As Camus puts it: “I therefore conclude that the meaning of life is the most urgent of questions.”

Camus argues that life is meaningless and absurd. I wonder what Meursault thinks that his purpose is. He doesn’t have that much of an identity, and what little individualism he has is very weak.

Livia ^

DeleteAt this point in the story I have begun to feel less and less empathetic towards Meursault mainly because his passiveness and complete disregard for everything and anything that is going on around him is so absurd and I am absolutely perplexed at how someone could go through so much in his own personal life like the death of a mother, a possible upcoming marriage, a dangerous friendship with a pimp, new job opportunities and a connection with a neighbor who lost a beloved pet causes absolutely no emotion in his soul. I consider myself to be a very emotional person so i’m always the one who cries during the sad part of a movie or has difficulty with a lot of social change in my life and so it just seems so off that Meursault can just live his life so unattached to everyone and everything.

ReplyDeleteI also feel like this might be introducing a theme that Camus might be trying to relay in this story. Through these absurd scenarios in which Meursault has no feelings or emotions, Camus may be trying to shine light on the fact that so much of our own human experience and life depends not so much on the event that happens, but more so on how we feel and react to that event and everything that follows after it. This can be tied into Sartre’s existentialism and how people are responsible for their own decisions and choices but also have to use their own personal morals and values to make the best and right decision for that situation. In addition to this in existentialism one must take blame for their actions and mistakes but it truly seems like Meursault is oblivious to everything around him and does not realize when he upsets people and does not even care enough to make the people around him “feel better” it’s all just about his own self gain. I think a good example of this is when Marie, “ just wanted to know if I would have accepted the same proposal from another woman, with whom I was involved in the same way. I said, ‘Sure’”. These are quite hurtful words to hear from someone who you could possibly marry in the near future and Meursault obviously saw nothing wrong with saying that he would be fine with dating another girl like Marie and never thinks once to apologize. He does not take responsibility for his wrongdoings as an existentialist should.

This comment has been removed by the author.

ReplyDeleteOriginal Version: 2/14

ReplyDeleteRenewed Version:

Camus claims that the meaning of life is the most critical question. While our lives may continue if we accept those reasons to live, our lives are alienated from the world if we reject them. This feeling of separation due to the denial of meaninglessness is an absurdity. In The Stranger, Camus tells us the essence of life is meaningless, and human existence is absurd. People don't need to follow and be restricted by any existing morals or rules but accept the trivial and absurd to gain meaning and valuable lives.

In the Stranger, Camus uses Meursault's reactions and attitudes to describe his existential philosophy. He believes that human existence is absurd in that there is no higher meaning or moral value to it. Meursault is cold, detached, and indifferent about his mother's death, and calmly accepts the absurdity of everything his life gives to him. When he was with his friend Raymond, "[Meursault] tried ... to please Raymond because I didn't have any reason not to please him." When Meursault's girlfriend Marie asks him if he loves her, he "told her it didn't mean anything." He also doesn't care if he marries her or not. Meursault answers Marie in complete honesty, not using circumlocution nor conforming to societal expectations. Without any moral compass, Meursault is indifferent to his fellow beings. There is no real reason to act or not to act in any given situation. Meursault accepts what he has been given.

On the other hand, Camus encourages revolting against the absurd life, living without higher purpose, and living without appeal. He depicts the essence of the human condition in The Myth of Sisyphus. He is condemned to everlasting torment to roll a rock to the top of a mountain endlessly as the stone would fall. His labor is futile, and his work and life are absurd. However, Sisyphus continues doing it even though he knows every success is a failure. He despises the meaninglessness and absurdity, yet accepts them as the essence of life and becomes the master of his fate.

Comparing Camus' attitude of accepting absurdity without emotions as a protest against meaningless lives, Sartre believes their choices and actions define the meaning of humans after they were born. Sartre thinks that people will suffer in anguish, forlornness, and despair from what they have received. When a man realizes life is meaningless without a predetermined purpose, he has to commit himself to everything. He anguishes purely due to his direct responsibility towards himself and other people as "a legislator deciding for the whole of mankind." Without meaning, there's no morality, and people no longer have decency or commands as justifications of behaviors or measurements in the realm of values. Men no longer have a future to fantasize about. They are free but are abandoned in despair. Sartre's version of existentialism is filled with human emotions and their struggle to accept the absurdity of life.

In our lives, we have been encouraged to have our dreams and ideals. Existentialism tells us the dreams may be beautiful but the reality could be far different and cruel. We must be ready to face and accept various possibilities in life.

All of Camus' ideas do connect to each other very naturally. Meursault does not consciously make it an effort to force his ideas constantly through his head, but his narration does give the reader a good idea of where his psyche and ideas lie. Meursault made it clear that he does not believe in a god because of his bashing of any religious symbolism at his mother's funeral (I affirm that there was cynicism because the mother and himself were both not religious). Meursault does everything that he does because he wants to. He never gives into peer pressure, nor does he give into the "rules" of society because it is of no gravity to him. Meursault is the definition of zero gravity: All events and choices have a mass, but because Meursault has no gravity, the weight of all events comes out to zero. It has no power over him unless he decides he wants it to. I draw a lot of freedom from Camus' of life and how none of this actually matters. Rather than base my life on a tragedy that I am not immortal, nor is the idea of me, I choose to live a life where my actions are determined by my desire. I like to help other people, it makes me happy because the joy I bring to other people makes me personally happy, so I choose to help other people out of my own selfish and personal desires. Perhaps I could say that I am lucky that I draw my personal gratitude and satisfactions from the joy and optimism of others rather than the taste of cigarettes or the cruelty of animals, but one could argue that all actions are exactly the same in essence. My joy of ambition and success carries the same power as someone's ultimate joy of eating batteries. All actions are the same. I don't have to write this blog response, and I know I don't. Of course there are actions to me not finishing this blog response: My grade will go down, I won't be able to participate in class, and I could end up feeling a little left out. But, just because I have the freedom not to write this blog response doesn't mean I don't want to. My desire to write this blog response does exist. I know it will please the teacher, I'll be able to exercise and stretch my ideas better, and ultimately it will make me more intelligent by writing my ideas out. Who is anyone else to tell me that my desires are incorrect or I am lying? What reason do I have to lie about something so trivial as a single blog post on this day of February in the year 2020? I have no reason to listen to them, thus extending my point on the action of my writing this. Maybe if everyone acted on their own desires and not the by the force of society's will, then we could live in a better world. One could beg the question that if everyone were to do whatever one pleased, that murder, rape and theft would run rampant. I argue that this is not true. I say that very few people desire to rape or murder someone, but if YOU saw someone being killed or raped, would you not run to protect them? You don't have to, but if you wanted to help them you could, there is nothing holding you back. I suggest Emma Goldman's essays for everyone's consideration.

ReplyDeleteThere is a notable difference between Sartre’s and Camus’ interpretation of existentialism. Instead of what Sartre sees as humans possess and “cannot help escape the feeling of his total and deep responsibility” (Sartre), Camus believes humans have “this feeling of separation from the world.” Indeed, Monsieur Meursault is unable to form lasting, meaningful connections between other people and lives for pleasure alone. This sense of removal is highlighted when Meursault decides act as Raymond’s witness, which “doesn’t matter to [Meursault]” (Camus 37). There is no doubt that Meursault had heard and knew about the abuse that had been occurring. However, because Raymond asked/ decided for Meursault that he would be his witness, Meursault obliged, swayed by the current. It is questionable if Meursault even cares about the fate of Raymond, and if he would actively help his acquaintance if Raymond required assistance.

ReplyDeleteSuicide and the purpose of life is of great importance to Camus. Humans “know that we feel, but our knowledge of ourselves ends there” (Camus). That is all that Meursault lives for. He engages in feeling of pleasure with his girlfriend, at Celeste’s, and at the beach. However, Meursault applies no meaning to any of these actions, not reciprocating any feelings of love or friendship to those he interacts with. This lack of uncaring and forced isolation also align with the Myth of Sisyphus, where Sisyphus’ “‘passion for life won him that unspeakable penalty in which the whole being is exerted toward accomplishing nothing’” (Camus). However, it remains to be seen if Meursault wishes to pursue life, when he is questioned about the murder of the Arab. It is evident that life is treasured by Meursault, for he doesn’t commit suicide, despite his lack of purpose in life, where base human sensations are enough to sustain him.

Camus finds that “we can live without faith, without hope, and without appeal”(Camus) and “we can revolt against the absurdity, and find some small modicum of happiness (Camus).” Whereas Sartre’s beliefs tend towards darkness, Camus argues that life can still be good, and we need not be resigned to any fate. When the purpose of life becomes convoluted, as it differs for each individual, Camus strips away all the differences and extraneous desires to reveal the bare minimum in “The Stranger.” Personally, this kind of life is unfulfilling, and would require a great sense of self assurance to life.

Camus explains his personal theories on existentialism through literature by making use of extended metaphors and allegories through The Stranger and The Myth of Sisyphus. Through these vessels, he demonstrates life as well as death’s meaning (or lack thereof). His theory builds on Sartre's theory of existentialism by relating distinct moments that occur in Meursault’s life or in the myth to correlate with ideas emphasized by Sartre in his existentialism essay. For example, Camus writes, “A minute later [Marie] asked me if I loved her. I told her it didn’t mean anything but that I didn’t think so.” This shared parallels with “man will only attain existence when he is what he purposes to be. Not, however, what he may wish to be” where Sartre believed that one truly “lives” or “exists” if they give meaning or purpose to their thoughts, ideas, and actions. As I have previously explained for Chapters 1-3 of Part One, Albert Camus doesn’t make Meursault possess a certain volition or drive so the question remains is whether he truly exists in his plane of life.

ReplyDeleteAnother example can be denoted with this quote: “I said that people never change their lives, that in any case one life was as good as another and that I wasn’t dissatisfied with mine here at all.” Meursault’s view on the meaning of a life connects to his (lack of) morality which pushes him further away from the Sartre’s definition of a true existence. “However, if we are to have morality, a society and a law-abiding world, it is essential that certain values should be taken seriously; they must have an a priori existence ascribed to them.” Also, Camus creates religious parallels to Sartre’s essay on existentialism related to atheism. Meursault says “I had only a little time left and I didn't want to waste it on God.” Relates to “Existentialism is nothing else but an attempt to draw the full conclusions from a consistently atheistic position.“

I saw myself in “The Stranger” when Meursault replies that it is all the same to him, and his boss becomes angry at his lack of ambition. Meursault muses that he used to have ambition as a student, but then realized that none of it really mattered. “For Camus killing yourself is admitting that all of the habits and effort needed for living are not worth the trouble. As long as we accept reasons for life’s meaning we continue, but as soon as we reject these reasons we become alienated—we become strangers from the world.” As long as I have a purpose in terms of my vocational and relationship goals, I need not feel like my life was wasted. Everything is utterly subjective.

Based on the summary of “The Myth of Sisyphus”, Camus proposes the idea that life is a struggle for balance between living with meaning, versus “without faith, without hope, and without appeal.” I see this philosophy clearly portrayed in “The Stranger”. Like I have said in previous entries, Meursault is the most blank of canvasses in terms of character. By having a main character that acts seemingly habitually, Camus shows readers the extreme of his philosophy. Meursault has no morals, no hope, no faith. He simply floats through life, acting on what Camus refers to in “The Myth of Sisyphus” as continuing “to live out of habit.” However, whereas Camus may describe Meursault’s lifestyle as “absurd”, he simultaneously defines it as “free” in the same sense that Sartre’s “forlornness” of god makes us truly independent. He states “In this sense we are free--living without higher purposes, living without appeal.” We may bash Meursault for the lack of meaning behind his actions, but without morals and this meaning, he truly is free beyond our perspective. It is in this detachment from meaning that I see most in my life. Sometimes, it is just easier not to think about what something means, and to just do. For example, it has always fascinated me how the way a soldier prepares themselves for war may very well determine whether or not they are traumatized afterwards. Yes, some may assert that the horrors they have witnessed or committed hold meaning in a positive sense, such as a veteran who believes the lives he took resulted in the saving of others. However, in such coping, Camus’ absurdity can also be applied. Many other soldiers may simply detach themselves of all meaning, and live on instinct simply in order to avoid a train of thought that would otherwise destroy them. Meursault feels no guilt for having killed the Arab. Neither do soldiers that detach meaning from their duty.

ReplyDelete